Selection of Snuff Boxes

Snuff Boxes - Looking at lids - by Juliet fynes

Due to constraints of space we have only cylinder boxes, and about half this ‘proper collection’ (that is excluding my toys and novelties) consists of miniature snuff-box type movements, or tabatières if you will (everything sounds much grander in French). Constraints of finance mean that most are fairly modest, no precious metals, jewels or enamels – alas! Our prize exhibit has a beautifully painted miniature on the lid. This box was featured in issue 1 of “Mechanical Music World”, with much technical detail. I hate to shock the purists among you but I must confess to being rather more interested in the cases than the movements!

Some items in our collection are in tortoiseshell cases, a few “orphan” movements have been housed as best we can, but most fall into two categories; tin boxes and pressed reconstituted horn or composition snuff boxes. They have good, even very good, movements but what particularly appeals to me is the great variety of lid decoration.

Some items in our collection are in tortoiseshell cases, a few “orphan” movements have been housed as best we can, but most fall into two categories; tin boxes and pressed reconstituted horn or composition snuff boxes. They have good, even very good, movements but what particularly appeals to me is the great variety of lid decoration.

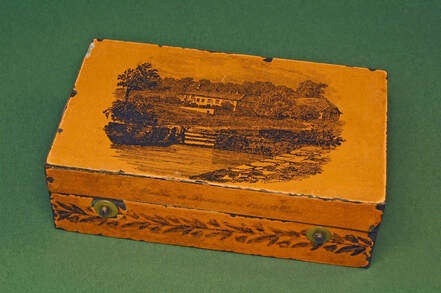

Fig 1

Fig 1

The tin boxes are so humble-looking that, although a musical box enthusiast can spot one at fifty paces, the average person would think it was for pins or pills and be amazed at what lurks inside. My first one, bought many years ago with beginner’s luck, was an early sectional-comb movement by L Golay, fitted in an orange box with a transfer view of an old building in a rural landscape which, unusually, bears the artists name, Th Rausches (Fig 1). The inscription on the side of the lid is rather faint, but it is possible to make out “Maison de Rousseau” followed by an illegible place name. Internet research only turned up his birthplace in Geneva and a country house in Les Charmettes, where he stayed. Definitely not either of these. Then by one of those happy coincidences, when visiting friends for a musical box session, I asked if they had any miniature movements and one of the three tin boxes produced was almost identical to mine. There it was clearly printed “Maison de Rousseau à l’Ile St Pierre”. More research uncovered that the building is a former monastery where Rousseau’s room can be visited. Sadly, although he said it was the place where he had been happiest, he was only able to stay for two months before being expelled for his religious views. My friends’ little box contains a one piece movement by H Lecoultre but by another coincidence they also have a sectional comb movement by L Golay, but this is housed in a composition box with a view of Geneva.

I was long ago told that this first acquisition was an example of a “transit” box, made to protect the movement as it was sent away from Switzerland to be put in a more elaborate and costly box by a jeweller. I later discovered that there were completely plain tin boxes used for this purpose, which made more sense. Why decorate, even quite cheaply, what was just the packaging? The first half of the 19th C, towards the end of the era of the “grand tour” of Europe, made by rich and aristocratic foreigners, coincided with the growth in continental rail travel by the rather less wealthy middle classes. It seems very likely that the musical box makers seized the opportunity of exploiting a new market for their miniature movements by making them into souvenirs, in inexpensive tin boxes decorated with prints of local views.

Something similar certainly occurred in England and Scotland a little later in the nineteenth century. When the Goss china factory in Stoke-on-Trent, and the Smith family company in Mauchline, needed to diversify they were able to capitalise on the expansion of rail travel for the masses, which fuelled a desire for small, inexpensive, mementoes. The family ceramics firm of Goss introduced small china souvenirs, bearing the crests of towns and seaside resorts. These were so popular they soon became their only product and were swiftly emulated by other china factories. The Smiths, who had been predominantly makers of snuff boxes, began to suffer as the fashion for snuff taking declined. So they turned to making transfer printed wooden souvenir wares. These, widely known as “Mauchline Ware”, also proved very successful.

I was long ago told that this first acquisition was an example of a “transit” box, made to protect the movement as it was sent away from Switzerland to be put in a more elaborate and costly box by a jeweller. I later discovered that there were completely plain tin boxes used for this purpose, which made more sense. Why decorate, even quite cheaply, what was just the packaging? The first half of the 19th C, towards the end of the era of the “grand tour” of Europe, made by rich and aristocratic foreigners, coincided with the growth in continental rail travel by the rather less wealthy middle classes. It seems very likely that the musical box makers seized the opportunity of exploiting a new market for their miniature movements by making them into souvenirs, in inexpensive tin boxes decorated with prints of local views.

Something similar certainly occurred in England and Scotland a little later in the nineteenth century. When the Goss china factory in Stoke-on-Trent, and the Smith family company in Mauchline, needed to diversify they were able to capitalise on the expansion of rail travel for the masses, which fuelled a desire for small, inexpensive, mementoes. The family ceramics firm of Goss introduced small china souvenirs, bearing the crests of towns and seaside resorts. These were so popular they soon became their only product and were swiftly emulated by other china factories. The Smiths, who had been predominantly makers of snuff boxes, began to suffer as the fashion for snuff taking declined. So they turned to making transfer printed wooden souvenir wares. These, widely known as “Mauchline Ware”, also proved very successful.

Fig 2

Fig 2

Contemporary with the tin boxes were composition snuff boxes with designs impressed on the lids. My interest is mainly in the decoration but I have also become curious about their manufacture. Were they ever intended for snuff? I have read that there is seldom, if ever, any trace of snuff to be found in them and that the shaped inner cover of translucent horn was to provide a place to store the key. The word “composition” is not very specific. It is used in this context to describe a material that was malleable when heated so that it could be pressed into a mould. Looking at these boxes it seems that the recipe for the composition materials must vary as they present differences in appearance. Some are an intense black, smooth and shiny. These are usually earlier, smaller and the moulded pictures on the lids often have a typically dainty “Regency” look to them, such as flower motifs in an oval cartouche (Fig 2).

Mythological and classical tableaux were also popular.

Whereas the tin boxes housing small movements were a new concept, almost certainly aimed at the tourist market, the composition boxes came about through a desire to economise. Earlier boxes were often made of tortoiseshell (actually the shell of the hawksbill turtle) or horn. Then, to reduce the cost, sometimes a mixture was made from the ground shell or horn, with animal glues coloured with lampblack. The use of pressed horn for small decorative objects goes back to medieval times. The heating of horn makes such a stench that the City of London decreed that horners should be located outside the city limits.

The evidence seems to suggest that the earlier reconstituted horn/tortoiseshell boxes were sold as gifts or trinkets in shops such as jewellers. Inside the lid of the box in Fig 2 there is a shop label “Wales & McCulloch, Jewellers, 32 Ludgate Str., London”. The development of various cheaper composition materials must have come as a relief, not least to the poor old turtle hunted almost to the point of extinction. These later snuff boxes are often overtly tourist orientated, decorated with views or famous buildings. They are usually somewhat larger and the material has a duller brownish black and even slightly speckled appearance. Classical scenes remained popular, but were generally less sharply moulded than on the earlier boxes. The movement are of more variable quality as the makers strove to widen the market by making cheaper products. At the same time European rail travel was becoming even more accessible. In 1847 Bradshaw published his first Continental Railway Guide and in 1863 Thomas Cook conducted his first tour of Switzerland.

In the middle of the nineteenth century numerous composition materials were developed for industrial and decorative uses. As the musical snuff boxes were apparently intended for the French market, my first thought was of bois durci, made from blood and powdered wood, patented in 1856 by F. C. Lepage of Paris. But many composition boxes predate this. Another possibility is gutta percha, hardened latex. It originated in Malaysia but was brought to this country in 1843. Its uses were many and varied, based on its three particular properties; its plasticity exploited in the manufacture of early golf balls; its insulating properties in the coating of electrical cables; and its low coefficient of thermal expansion in the making of moulds and castings. This last enabled great detail to be included in the mould. The Gutta Percha Company was established in Britain in 1845 and made many decorative items such as chessmen, plaques and animal figures, but probably not musical box cases as these appear to have been of French manufacture. In 1852 Francois Joseph Beltzung of Paris, took out a patent for machinery for the pressing and moulding of gutta percha, so may well have been the source for some of the cases.

Shellac, made from the secretions of the lac beetle, is mainly known as a protective coating but shellac compounds were used in the manufacture of decorative items from the mid 1800s. A compound, including lampblack, was used in the manufacture of gramophone records before the invention of vinyl. I have seen a new lid for a snuffbox made from an old record, with just the slightest trace of the grooves still visible. Vulcanite, a hardened rubber, first made in the USA in 1839, was also widely used in decorative mouldings, especially jewellery to simulate jet, but was duller in appearance.

The development of these, and other, different composition materials, which were usually black or very dark, and capable of taking quite detailed moulding, led to the production of a variety of decorative items as well as their more utilitarian uses. There are manufacturers’ lists of these; everything from buttons to vesta cases, brooches to daguerreotype frames. I have not been able to find any mention of musical box cases but one or more of these new compositions must have been used. The only case-makers name I have come across is F Morel.

Having started speculating on the materials used I also noticed a variation in the hinges. The tortoiseshell boxes usually have a metal hinge the full width of the case, as do most of the smaller, earlier composition boxes. The later, larger ones mostly have the hinge parts moulded into the lid and base with a metal pin going through, although there are some later boxes with metal hinges and earlier ones with the moulded hinge. I have already mentioned Mauchlineware and these so-called “hidden” or “secret” hinges were a feature of their wooden snuffboxes. This invention is generally credited to James Sandy of Alyth, a few miles north of Dundee, in the late 18th or early 19th century. Manufacture was taken over by Charles Stiven from nearby Laurencekirk which is over a hundred miles from Mauchline, a very considerable distance at that time. A story goes that a French gentleman took one of these Laurencekirk snuffboxes for repair to a William Crawford of Cumnock, not far from Mauchline. Crawford managed to work out how the hinge was made and began to manufacture these snuffboxes himself and the secret soon spread to other snuffbox makers in the area. It may be a step too far to surmise that the unknown Frenchman might have taken the secret back home to France with him, to then be incorporated in musical snuff boxes.

Mythological and classical tableaux were also popular.

Whereas the tin boxes housing small movements were a new concept, almost certainly aimed at the tourist market, the composition boxes came about through a desire to economise. Earlier boxes were often made of tortoiseshell (actually the shell of the hawksbill turtle) or horn. Then, to reduce the cost, sometimes a mixture was made from the ground shell or horn, with animal glues coloured with lampblack. The use of pressed horn for small decorative objects goes back to medieval times. The heating of horn makes such a stench that the City of London decreed that horners should be located outside the city limits.

The evidence seems to suggest that the earlier reconstituted horn/tortoiseshell boxes were sold as gifts or trinkets in shops such as jewellers. Inside the lid of the box in Fig 2 there is a shop label “Wales & McCulloch, Jewellers, 32 Ludgate Str., London”. The development of various cheaper composition materials must have come as a relief, not least to the poor old turtle hunted almost to the point of extinction. These later snuff boxes are often overtly tourist orientated, decorated with views or famous buildings. They are usually somewhat larger and the material has a duller brownish black and even slightly speckled appearance. Classical scenes remained popular, but were generally less sharply moulded than on the earlier boxes. The movement are of more variable quality as the makers strove to widen the market by making cheaper products. At the same time European rail travel was becoming even more accessible. In 1847 Bradshaw published his first Continental Railway Guide and in 1863 Thomas Cook conducted his first tour of Switzerland.

In the middle of the nineteenth century numerous composition materials were developed for industrial and decorative uses. As the musical snuff boxes were apparently intended for the French market, my first thought was of bois durci, made from blood and powdered wood, patented in 1856 by F. C. Lepage of Paris. But many composition boxes predate this. Another possibility is gutta percha, hardened latex. It originated in Malaysia but was brought to this country in 1843. Its uses were many and varied, based on its three particular properties; its plasticity exploited in the manufacture of early golf balls; its insulating properties in the coating of electrical cables; and its low coefficient of thermal expansion in the making of moulds and castings. This last enabled great detail to be included in the mould. The Gutta Percha Company was established in Britain in 1845 and made many decorative items such as chessmen, plaques and animal figures, but probably not musical box cases as these appear to have been of French manufacture. In 1852 Francois Joseph Beltzung of Paris, took out a patent for machinery for the pressing and moulding of gutta percha, so may well have been the source for some of the cases.

Shellac, made from the secretions of the lac beetle, is mainly known as a protective coating but shellac compounds were used in the manufacture of decorative items from the mid 1800s. A compound, including lampblack, was used in the manufacture of gramophone records before the invention of vinyl. I have seen a new lid for a snuffbox made from an old record, with just the slightest trace of the grooves still visible. Vulcanite, a hardened rubber, first made in the USA in 1839, was also widely used in decorative mouldings, especially jewellery to simulate jet, but was duller in appearance.

The development of these, and other, different composition materials, which were usually black or very dark, and capable of taking quite detailed moulding, led to the production of a variety of decorative items as well as their more utilitarian uses. There are manufacturers’ lists of these; everything from buttons to vesta cases, brooches to daguerreotype frames. I have not been able to find any mention of musical box cases but one or more of these new compositions must have been used. The only case-makers name I have come across is F Morel.

Having started speculating on the materials used I also noticed a variation in the hinges. The tortoiseshell boxes usually have a metal hinge the full width of the case, as do most of the smaller, earlier composition boxes. The later, larger ones mostly have the hinge parts moulded into the lid and base with a metal pin going through, although there are some later boxes with metal hinges and earlier ones with the moulded hinge. I have already mentioned Mauchlineware and these so-called “hidden” or “secret” hinges were a feature of their wooden snuffboxes. This invention is generally credited to James Sandy of Alyth, a few miles north of Dundee, in the late 18th or early 19th century. Manufacture was taken over by Charles Stiven from nearby Laurencekirk which is over a hundred miles from Mauchline, a very considerable distance at that time. A story goes that a French gentleman took one of these Laurencekirk snuffboxes for repair to a William Crawford of Cumnock, not far from Mauchline. Crawford managed to work out how the hinge was made and began to manufacture these snuffboxes himself and the secret soon spread to other snuffbox makers in the area. It may be a step too far to surmise that the unknown Frenchman might have taken the secret back home to France with him, to then be incorporated in musical snuff boxes.

In considering the material and construction of these boxes I have digressed from my original intention to focus on the lid decoration. The tin boxes remained substantially the same over a lengthy period. They were mostly orange, green or yellow, and more rarely red or blue, and contained good quality movements. Most bear prints of buildings or views, usually of the St Croix and Geneva areas, though I have seen illustrations of boxes depicting Italian cities, and one with a battle scene. Also some have paintings of views or bucolic interiors on the lids but these are less common. The decoration on the lids of composition boxes, and the quality of the movements, is more varied. On earlier boxes the illustration is generally finer and less overtly tourist orientated. Mythological and classical scenes were popular throughout the era with the same scenes being depicted rather more crudely on later boxes. “La Mort de Socrate” from a painting by the French artist Jacques-Louis David is such a one. A friend owns a small early box, made by Vacheron et Constantin, with this scene finely executed. We have a later and somewhat larger composition box with the same scene, the maker of the movement is unknown but the name F Morel is embossed on the lid (Fig 3). Another friend owns a similar box with “Le Triomphe de Galatee” from the painting by Raphael. The name F Morel also occurs on a tortoiseshell box of ours bearing a rectangular embossed gilded panel showing “The Last Supper”. I have seen a similar box illustrated in an old auction catalogue and also one with an oval enamel plaque. Interestingly on the inside of the lid of our gilded example can clearly be seen an oval outline, as though the plaque was the original intention, but the rectangular panel for some reason was used instead. We have also recently acquired an ordinary snuff box with a similar panel showing “L'entrée de Jésus dans Jérusalem”, with the intention of transferring this to a tortoiseshell musical box which is missing its panel. I have been unable to discover anything about Monsieur Morel but there were several French jewellers bearing the name, who may or may not have been related. He must have been a prolific maker of composition cases, judging by the high proportion of his amongst the examples I have seen. He catered to a wide range of tastes from the artistic to the devout, the humorous to the frankly macabre, as in the picture of bear baiting, where twelve dogs and two bears are savaging each other.

I find particularly interesting the illustrations of what I presume to be French jokes. One has two soldiers in a farmyard chasing a pig, which one soldier has by the tail, the other near a gate and the words “Tiens Ferme”. Another box has two soldiers outside a henhouse, one luring a chicken with some grain, the other with his sword poised to cut it down when it emerges, with the words “Petits, Petits, Petits“. Yet another shows an officer holding a bird in a cage in front of three soldiers, one of whom is falling backwards, captioned “Mon Caporal J’nai Pu Avoir Que Ca!....” Does this type of illustration always depict soldiers in farmyards? Do they refer to some political events, such as the satirical pictures often appearing on pottery of this era, both here and in France? I should love to know.

The lid of my most recent acquisition is decorated with masonic symbols. The central motif is “The Pelican in her Piety”, which is associated with Rosicrucianism, a medieval secret society, which inspired the masonic “Scottish Rite” first practised in France, indicating that this box was probably also made for the French market.

From my, admittedly small, sample I have concluded that the tin boxes were introduced to sell in Switzerland to the new wave of tourists. Whereas the composition boxes, significantly cheaper than tortoiseshell, enabled French manufacturers to house imported movements to cater to their tourist trade.

I have a tin box with a view of Milan. Are any tin boxes known with French views? Are views from any other country depicted on either tin or composition boxes? Have you a composition box with a military “joke”. Are there boxes for other special interest groups such as the Masons? Did anyone other than F Morel sign his cases?

I find particularly interesting the illustrations of what I presume to be French jokes. One has two soldiers in a farmyard chasing a pig, which one soldier has by the tail, the other near a gate and the words “Tiens Ferme”. Another box has two soldiers outside a henhouse, one luring a chicken with some grain, the other with his sword poised to cut it down when it emerges, with the words “Petits, Petits, Petits“. Yet another shows an officer holding a bird in a cage in front of three soldiers, one of whom is falling backwards, captioned “Mon Caporal J’nai Pu Avoir Que Ca!....” Does this type of illustration always depict soldiers in farmyards? Do they refer to some political events, such as the satirical pictures often appearing on pottery of this era, both here and in France? I should love to know.

The lid of my most recent acquisition is decorated with masonic symbols. The central motif is “The Pelican in her Piety”, which is associated with Rosicrucianism, a medieval secret society, which inspired the masonic “Scottish Rite” first practised in France, indicating that this box was probably also made for the French market.

From my, admittedly small, sample I have concluded that the tin boxes were introduced to sell in Switzerland to the new wave of tourists. Whereas the composition boxes, significantly cheaper than tortoiseshell, enabled French manufacturers to house imported movements to cater to their tourist trade.

I have a tin box with a view of Milan. Are any tin boxes known with French views? Are views from any other country depicted on either tin or composition boxes? Have you a composition box with a military “joke”. Are there boxes for other special interest groups such as the Masons? Did anyone other than F Morel sign his cases?

So many questions. If you have any answers I should love to hear them. Also please feel free to challenge any of the assumptions, inferences, and wild guesses I have made.

More articles coming soon