Small Chamber Barrel Organs from The British Aisles & France by Anna Svenson

Barrel organs are an extremely old form of mechanical music. Organs are mentioned in the Bible and there are writings on them before this. The Bible claims that the pneumatic organ was the work of Jubal and David. The Roman Church attributes St Cecilia as the true inventor. Muslim writers attribute Aristotle (344BC). There are many references to elaborate instruments of different designs such as automatic hydraulic organs and the water driven, mechanically operated organ built by the Bana Musa in the ninth century which only had one pipe and had pallets along its length to open and close the holes to produce the different notes.

With the invention of clocks and clockwork, the organ was soon incorporated into them. One of the most famous early examples was a present from Queen Elizabeth 1 to the Sultan of Turkey. This was built by Thomas Dallum in 1599. This was not a small clock! It stood about twelve feet six inches high, five feet six inches wide and four feet six inches wide and was very elaborate (this is an understatement, ie: a carved figure of Queen Elizabeth with diamonds, rubies and emeralds, moving figures, etc!).

Many churches have organs and in the past it became obvious that a barrel organ could be turned to play the selection of hymns on the barrels, one turn for each verse. This meant that the organist did not have to be present. Gradually, by the middle of the eighteenth century, chamber barrel organs, made to look not out of place in well-to-do homes, were being produced as a means to play music mechanically in the home by merely turning a handle and pulling out stops to bring in the different ranks of pipes, a rank being a set of pipes of similar timbre tuned to a scale. These ranged in size from the floor standing organs, with stops on the front or side which would bring in wooden or metal ranks of pipes and sometimes triangles and drums, to the little table-top organs having usually 11 or 12 wooden pipes, or occasionally fewer. Slightly larger table-top organs would accommodate barrels playing more notes than this, often with at least two ranks, so would have many more pipes. Often organs would have different barrels playing eight to ten dance tunes and tunes of the day on each barrel, and other barrels playing hymns for Sundays.

The small chamber barrel organs are mechanically very simple. A summary of how they work follows - apologies to those people who know this already! The winding handle drives a crank to work the bellows and a worm drive to drive the barrel. An arm called a reciprocator connects the crankshaft to the wind feeder, or two wind feeders, on the bellows which in turn supply the reservoir with air. A spring, sometimes two, or even a weight on earlier models, on the reservoir ensures a constant supply of air. The pipes at the back of the organ are inserted in line into the soundboard which forms the top of the windchest with pallets (leather faced wooden valves) inside it, one under each organ pipe, each having a very small spring keeping it closed which looks like an extremely thin open safety pin. If the barrel is removed from the organ, on turning the handle the air leaves the bellows along a channel called the windway and passes into the windchest. As no note has been instructed to play, as long as there is no air leak somewhere, the spill valve on the bellows should deal with the excess air and the notes should be silent – or there is a problem - cyphering! This can occur when the organ is playing music with the barrel and one or more of the notes will play continuously. Air is escaping round the pallet because there is some dirt between the pallet and the soundboard, the leather hinge on the pallet has become unglued, the pallet itself is defective, or the spring has broken or become displaced.

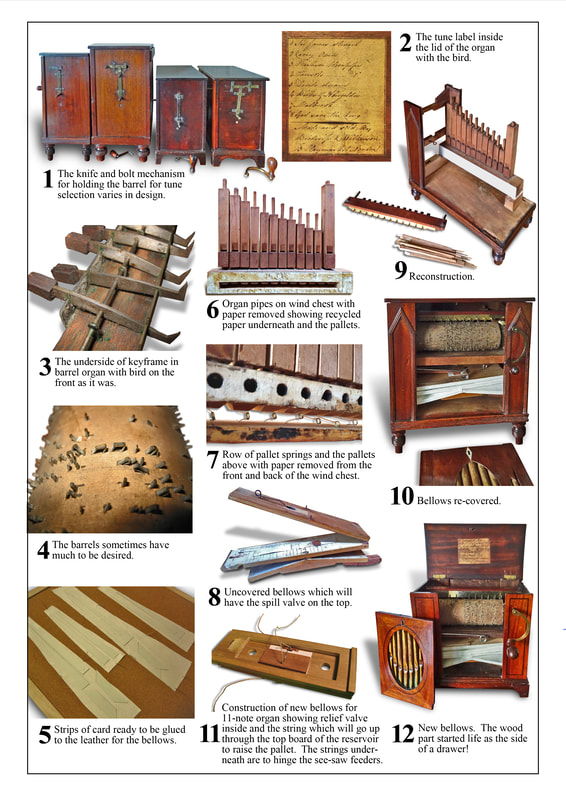

At the top of the organ is the keyframe holding the row of levers known as keys corresponding to the number of notes. These steel keys have hooks at one end which catch the brass pins and bridges on the barrel and all pivot on one length of wire which runs along the length of the keyframe. The tail end of each key ends in a very small block of wood which is hinged by a small piece of leather to a light weight, square sectioned stick known as a sticker. This has a thin wire inserted into its end which passes through a small hole into the windchest. As the key is lifted by a pin on the barrel, the key pivots and pushes the sticker down which opens the pallet allowing air out of the pressurised windchest and enabling the corresponding pipe to 'speak'. If there are more ranks of pipes these are selected using stops and each key will play all the pipes of that note which have been selected. The barrel will play usually from eight to ten tunes which are changed by moving the barrel one way or the other. There is a knife and bolt mechanism on the right-hand side of the instrument to hold the barrel in place and to raise the keyframe out of the way of the pins while the barrel is being moved.

The first small English chamber barrel organ I bought has a painting of a bird in a cage on the front and has twelve pipes. More often than not there is no maker listed anywhere on the organ, even if all the tunes are listed on a handwritten paper label under the lid which makes dating the instrument more difficult. As they often played the tunes of the day, dating can be estimated by investigating when the tunes were written. This one was made by Brodrip and Wilkinson and the address on the label 13 Haymarket, London, dates it from between 1798 and 1808 which is when they were working from this premises. However it did not work. I wanted to repair it without ruining it so spent more than a year looking at it and finding out more about them before I eventually took the plunge using traditional leather and animal glue which is strong but not permanent so that it can be restored in the future when the instrument is even older and more delicate. I find it very useful when old joints fall apart as it is easy enough to glue them together again and really difficult to restore when nothing will budge! The traditional hot glue is wonderful stuff and washes off paintbrushes, syringes and hands with water and if it has set it can be soaked off. New glue also sticks well to any of the old glue left behind as it becomes tacky when the hot glue is applied. I also find it useful before repairing anything to take lots of digital photographs of every angle and even photographs of the bellows with the old leather in place as it can be helpful to be able to look back at small details about how it was before it was dismantled.

The back legs were missing and had been replaced with two hollow cylindrical wooden ones so I started with the legs so that it would stand up. I had no idea what the notes were as I had not had one of these before and someone had pushed all the tuning stoppers on the tops down into the pipes! The reciprocator was broken and presumably the bellows did not have enough air at some time so the spill valve on the top to release excess air was glued down very firmly to prevent air loss! Most of the stickers were knocking around and the keys in the keyframe were stuck with gunge and Verdigris. The pins in the barrel had much to be desired!

The windchest in this organ is glued to the bottom of the case. Usually in these organs they are raised on small blocks which makes them much easier to remove. I eventually managed to extract it as it was necessary to reach one of the minute springs under a pallet as it was broken. Access to the pallets and springs is through the back of the windchest which is made of thick paper in the small organs. When I glued the windchest back in I put a very thin strip of leather under it which does not show as I thought it might be easier next time to remove!

The bellows are covered with a thin white sheepskin. These are glued on to very thick paper/thin cardboard, shaped like elongated triangles to keep them folding correctly which are hidden inside the bellows so do not show. The leather and cardboard can be used as a template for cutting out new ones. The spill valve on the top of this organ is a leather faced flap with a long wooden tail and held down with a spring. As the reservoir rises the tail eventually touches a horizontal pin which opens the valve to release excess air. These bellows were not lined with paper as some are. I did one bellows which were lined with what looked like handwritten accounts written with sepia ink. The paper on the back of the windchest were the same – recycled good strong paper!

A few years after purchasing this little organ I managed to find another one which was very similar but it had no winding handle, bellows or spring. There was an envelope inside with the postmark dated 1922 which contained some stickers and bits of the case. Presumably this is when someone started to restore it and then eventually passed on and the old tatty bellow parts and handle were lost by people who did not know what they were. I thought I could follow the design of the bellows I had in the first organ but things do not work out like that. There are two types of bellows in these little organs, the transverse type which has a single feeder below the reservoir and the rocking feeder known as a see saw which has two feeders. My original organ had the transverse type which I soon discovered would not work in the newly acquired one as the windway was far too high. The other thing I discovered was that there was no room for a spill valve with a tail so it had to have the other type of spill valve which is inside the bellows. As the reservoir rises a string, knotted or held with a small peg in the top board of the reservoir, passes through the board and lifts a pallet inside the reservoir which releases air back into both the feeders. Another organ I have has the see-saw bellows and the spill valve with a tail so it seems to be the preference of the maker.

The valves inside the bellows can vary as well as sometimes they are formed by a flap of leather, sometimes two pieced glued together under pressure to make them very flat, or the other type is made by one piece of leather across the hole, glued at both ends so that the air goes in down the sides and then is prevented from returning by the leather returning to lie against the wood.

The following shows the notes on the small organs that I have:

11 Note: G A B C C♯ D E F F♯ G A

12 Note F♯ G A B C C♯ D E F♯ G A B

12 Note F♯ G A B C C♯ D E F♯ G A B

12 Note D E F♯ G A B C C♯ D E F♯ G

14 note D E F♯ G A B C C♯ D E F♯ G A B (Two ranks, 1 wood, 1 metal)

(The underlined notes are large pipes placed at the right-hand end next to the high notes).

The three low notes on the 14 note organ are an octave lower.

11 Note: G A B C C♯ D E F F♯ G A

12 Note F♯ G A B C C♯ D E F♯ G A B

12 Note F♯ G A B C C♯ D E F♯ G A B

12 Note D E F♯ G A B C C♯ D E F♯ G

14 note D E F♯ G A B C C♯ D E F♯ G A B (Two ranks, 1 wood, 1 metal)

(The underlined notes are large pipes placed at the right-hand end next to the high notes).

The three low notes on the 14 note organ are an octave lower.

It can be seen that even with these three 12 note organs the notes are either different or that the first two have the same notes but the lower F♯ on the second one is inserted down next to the high notes.

Even if they were exactly the same size the barrels could not be interchanged as all the keys would be in the wrong place for the notes.

Even if they were exactly the same size the barrels could not be interchanged as all the keys would be in the wrong place for the notes.

The 11 note organ is the only one to have an F note. It is the only one to play 'God Save the King' in a different key! It plays in the key of C rather than the usual key of G. There are little organs which have different tuning scales to the ones I have.

The above instruments were all made in England or Scotland. I have recently purchased a small French barrel organ called a Serinette made by Husson-Jacotel fils ainé of Mirecourt. Pierre Francis Husson married the daughter of Auguste Jacotel 1790 – 1840 and I was informed by a French friend that 'fils ainé' specifically refers to the eldest son. Serinettes were first made in France in the first half of the eighteenth century and were played to teach canaries to sing. Indeed the word Serinette is derived from the French word 'serin' meaning 'canary'. The French verb 'seriner' means 'to keep saying the same thing, to tire out or to drum into', presumably by the serinette teaching the canaries and boring the human listeners to distraction! This one does not work yet..... There was a tiny bit of air, until the bellows split down the side, but most of the miniscule amount air that went to the windchest came out of the worm holes in the case! These work in the same way as the organs from the British Isles but are also different in many ways.

One of the main differences between this and the other British ones I have is that the pipes are made of a very soft metal whereas the organs I have, have wooden ones. Barrel organs which have more than one rank will often have metal ones as well as wooden ones, and the French made small organs with wooden pipes as well. The British chamber barrel organ is designed to sit on a piece of furniture with its back to the wall and be played from the front. The bass notes are on the left. The French Serinette has the bass notes on the right and the treble ones on the left. The ten pipes face the back of the instrument, suggesting that the rear panel should be removed when playing and the listener (or bird!) should be behind it.

The case of the small British Chamber organ is often decorated with faux gilded pipes on the front, the wood is commonly mahogany and the usually curved crank of the winding handle is made of brass, as is the crankshaft and worm gear inside. It will more often than not have legs. The French Serinette is made of walnut, this one has never had legs and the crank of the winding handle would have been steel as are the majority of the Continental instruments but the handle on this one has been replaced a while ago by something which looks as if it has been made by the local blacksmith!. The crank and worm gear are made of wood and the instrument appears to be more functional than an instrument for display. They were made between the middle of the eighteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century by most organ makers, the design changing little in this time, most being quite plain in appearance but some had decorative stringing and a few were extensively decorated.

As the Serinette appears to be meant to be heard from behind, the paper covering the side of the windchest is on the inside, making access very difficult. The bottom of the windchest and the bottom of the windway as well, is the bottom of the case! If it is possible to remove it – the springs will all fall out! If they need to be replaced they have to be replaced in situ – from the inside. Luckily in this organ I believe I will not have to do it!

The keyframe is made of a light coloured wood and the wooden keys, with their nail-like hooks hanging from beneath, by individual loops of wire. The British organs have a brass sheet screwed on to the front of the wood with slots cut into it to guide the keys and keep them in line. On the Serinette I have found that some of the loops of wire are bent so that the flattened nail-like projections do not track the correct line of pins on the barrel. What line? Bent pins on the barrel do not help!

The leather on the bellows appears to be original, but I am surprised to see, on looking through the hole that has appeared on the side, that there are no cardboard supports to hold it in shape but it appears to do so quite well without them. It could have been replaced but I have not seen inside the bellows of another serinette.

Three things I have found useful when repairing these instruments:

- Very downy feather – good for detecting where that leaking air is coming from.

- Thin tapered strips of ordinary white paper – to thread up the air slit in the front of the pipes for cleaning out bits of fluff and other rubbish without fear of damage.

- Basting implement for cooking with a small piece of soft flexible pipe stuck to the end – good for blowing puffs of air to blow debris away from small spaces. It also sucks – OK well …... I find it can be useful!